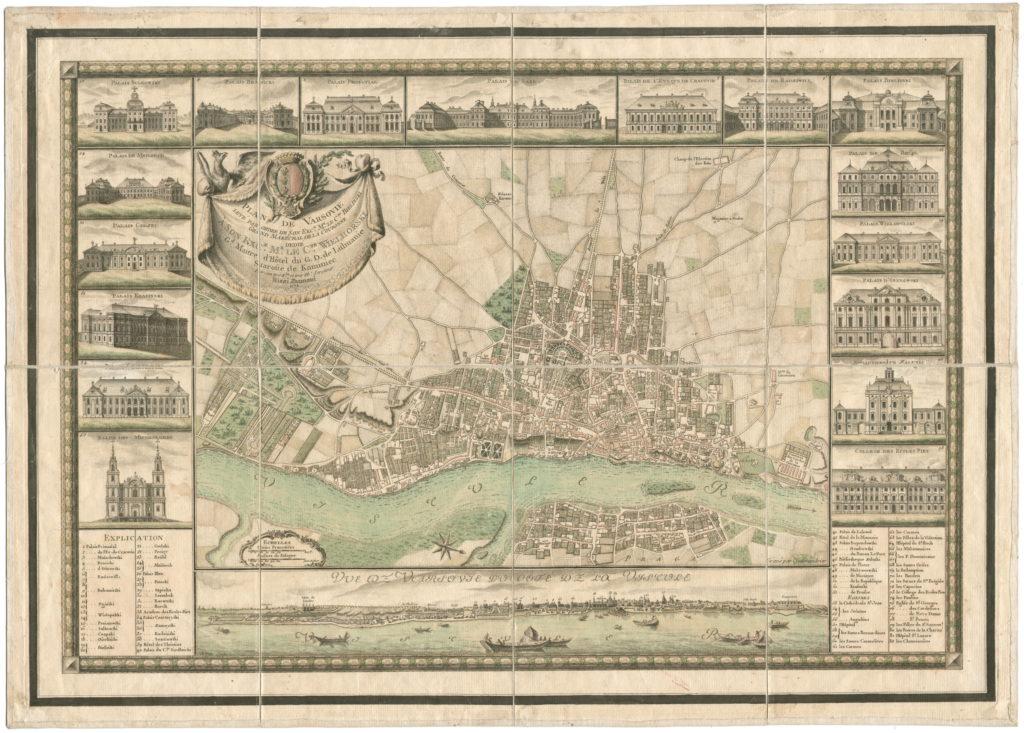

At first glance, Plac Żelaznej Bramy in Warsaw may seem like a chaotic patchwork of architectural styles and functions — but look closer, and it reveals itself as a vivid, layered case study in urban transformation. This square, nestled in today’s city centre, is not just a space, but a palimpsest: a place where 18th-century aristocratic ambitions, 19th-century commerce, wartime devastation and post-war socialist planning all leave visible marks on the landscape. Combining Baroque symmetry, market vitality, modernist towers and everyday life, Plac Żelaznej Bramy offers a living record of Warsaw’s urban and social history — an urban landscape both fragmented and deeply coherent in its testimony to change.

The first layer: the square’s beginnings and its character

The square was created in the 17th century as a market square. It was located on private land (a jurydyka) on the outskirts of the city at that time. ‘Jurydyka’ (from the Latin jurisdictio) was a legal term denoting land and a semi-rural area belonging to one of the Polish noble families. In the 17th and 18th centuries, such lands were numerous around what is now known as Warsaw’s Old Town. Due to the city’s development in the 19th and 20th centuries, these areas now correspond to the capital’s central districts.

The square owes its name to an iron gate in the garden, which was erected in 1724, demolished in 1818 and replaced with a smaller gate. The garden still exists, but the gate was dismantled after the Second World War.

The second layer: the life of the square in the 19th century and first decades of the 20th century – an important market square

The square retained its market character until the end of the Second World War. A large market hall was built there in the second half of the 19th century, which was destroyed during the war.

Two market halls had been built there at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. They were considered very modern at the time and still exist today.

The third layer: the Second World War and the second half of the 20th century

The Second World War was a very significant event in Warsaw’s history, resulting in the city’s widespread destruction. Innumerable old buildings were destroyed, and the urban structure was deeply affected. Many historic monuments were lost forever, while others were rebuilt or demolished and replaced with modern housing. The square bore witness to all of these events. During the Second World War, it was a market square, but it was also located on the border of the Warsaw ghetto, which was completely demolished by the Nazis after 1943.

One of the buildings reconstructed just after the Second World War was a Baroque palace. This resulted in the palace being restored to its original 18th-century appearance, rather than how it had been modified in the first half of the 20th century. In 1970 the decision was made to move the palace to a location that would emphasise the aesthetic value of the historic urban plan. Consequently, it was rotated by approximately 90 degrees. During this process, some parts of the palace were demolished.

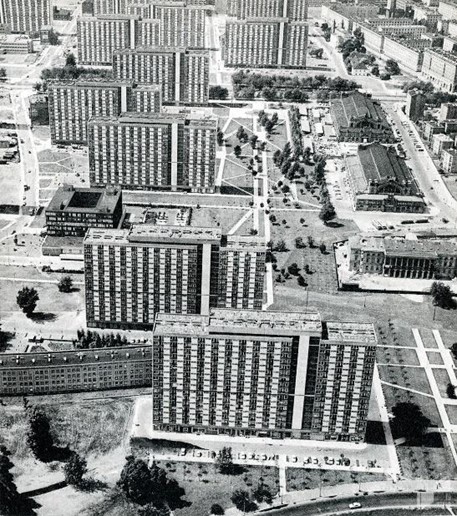

A housing estate was built in the 1960s and 1970s. It owes its name, Osiedle za Żelazną Bramą (Iron Gate Estate), to the square. It was designed to accommodate 30,000 people, who were expected to live in large, modern apartment blocks.

The fourth layer: the square today

Today, it is still an important market square. One of the halls (Hala Mirowska), which from 1953 hosted a renowned local sports club with boxing ring, fencing, basketball and tennis tournaments, was converted into a fashionable food hall in 2017.

Questions for students

A) Today’s look:

- What elements does the landscape contain (for example, a Baroque palace, 19th-century market halls, 20th-century blocks of flats and city greenery)?

- How do these elements fit together spatially? Which dominate in terms of scale and/or number? (For example, the market halls and new stands define the market space, while the palace separates the market from the park, and the surroundings are dwarfed by the modernist block of flats.)

- Do these elements form a coherent whole or instead are they a mix of diverse elements? Can distinct zones of the landscape be identified (for example, a modernist housing estate, two market halls and a park)?

- Can elements from different epochs be identified in the landscape? (For example, a Baroque palace from the 18th century, market halls from the 19th century and a block of flats from the 1950s [post-war reconstruction] and the 1970s [modernist ideals].)

- Is the landscape attractive to anyone? Who would like what? If so, why? (For example, the 19th-century market halls are spectacular, the Baroque palace and park are elegant, but the area as a whole may appear chaotic and inconsistent.)

- What sounds and smells dominate the landscape (for example, traffic, smells of goods offered at the market)?

- Is it a welcoming landscape?

B) Character and function:

- What is the landscape used for? (For example, commercial [market], recreational [park], representational [it’s at the end of a historic urban axis that is still visible despite the changes caused by the Second World War]).

- Who uses the landscape? Who can access it? (For example, the market is used by local people and district residents, while the park is rarely visited – it is located by a busy road and surrounded by housing blocks.)

C) History:

- Where does the name of the landscape come from, if there is one?

- What are the most important moments or stages in the landscape’s history?

- Are there any visible traces of history left? If so, do they impact the landscape’s current appearance and character?

- How has the character and functions within the landscape changed? Is there any historic continuity in the landscape?

- What historic and cultural (global and/or local) values can be identified?

- Who used the landscape in the past?

- Who inhabited the landscape in the past?

- What economic and social factors have shaped the landscape during subsequent historical periods?

Proofreading: Caroline Brooke Johnson