This lecture provides an introduction to the B-SHAPES project. It presents an overview of the rationale behind the B-SHAPES research project, its research objectives, activities, societal and political relevance.

B-SHAPES asks how borders shape our perceptions of society. When we are asked ‘where are you from?’ when travelling abroad, most of us will name the country they live in or feel attached to. This shows how our multiple identities merge into one, which is rather abstract, but rarely contested. It creates a perception of us, with plenty of stereotypes, which ultimately is shaped by a state border. But the border shapes in more ways than just the ‘where are you from?’ question. Through the border, we belong to an ‘imagined community’ (of citizens or at least residents of a country). Benedict Anderson (Anglo-Irish political scientist and historian who lived and taught in the United States. Anderson is best known for his 1983 book Imagined Communities) has developed this term to illustrate our perceived belonging to a community of which we do not know and never will know the vast majority of members, but nevertheless identify with (Anderson 1983). State borders thus shape belonging, a feeling of being home, Heimat (German: home).

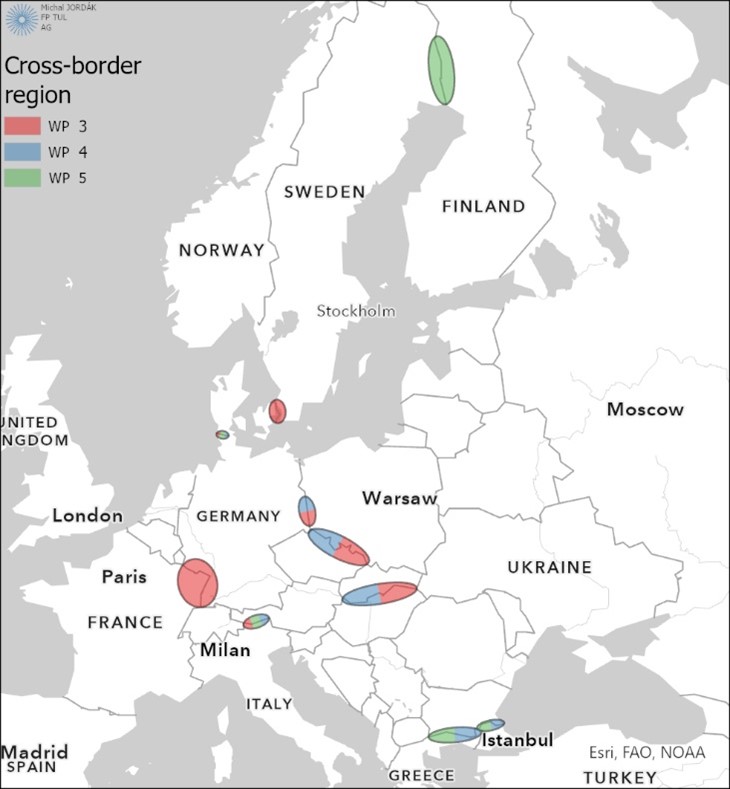

B-SHAPES aims to teach more about this connection, by focusing on the lesser heard voices in societal discourses on borders: the residents of borderlands. They are more affected by the physical state of a border than people living in central areas of the country. Communities as national minorities in borderlands, but also indigenous people like the Sami in northern Scandinavia may be separated from kin members by a state border and, therefore, subject to different perceptions shaped by this border. Additionally, we focused on Eurosceptics in borderlands, assuming they do not support the EU paradigm of open borders or ‘Borderless Europe’. A third dimension of the project explores the border landscapes. Landscapes or nature is not necessarily associated with borders and is often perceived as cross-border (that is, in the key argument to engage in cross-border cooperation, ‘pollution does not stop at borders’). Our research aims to learn more about how borderlanders connect the landscape they live in with the border. These learnings should help us how to obtain more inclusive, cross-border perceptions of regional and European society.

A history of states and borders

Why do we have states? Communities and societies build on a simple principle: individuals give up individual freedom for belonging and protection. In prehistory, human survival depended on belonging to a group – competing for food and resources with other groups, which forms the base of the ‘us’ and ‘them’ perception. ‘Us’ and ‘them’, also called the principle of ‘othering’, has never been static. Communities interacted with each other, increased in size and eventually settled and urbanised. Ancient Rome’s cultural model was attractive for outsiders, so it could integrate first the Italian peninsula and later the Mediterranean into an empire. Religiously legitimated rulers as the Islamic caliphs and the Holy Roman emperors managed to rule vast empires in an age of horses and sailing boats as means of transport and thus communication.

The Slavic term granica (German Grenze, Nordic grænse/gräns) describes a simple fence to protect a village/settlement. Early border demarcations are city walls, but also the Great (Chinese) Wall, as well as the Roman Limes Germaniae or Hadrian’s wall dividing the British island. These walls had a protective function, but they also served as a point of control of entry and exit, as well as a point of collection of taxes and duties and protected trade routes. This illustrates that borders divide as well as being meeting points. There is no consensus on the age of borders, but research indicates that a notion of territory was already present in prehistoric tribes and bands of hunters and gatherers.

The modern state border of today, though, is a later development. Borders in Europe have not been stable but changed frequently. A medieval map of Europe reveals a patchwork of kingdoms, princedoms, city republics like Venice or the Hanseatic League and clerical territories. They expressed land ownership rather than ethno-linguistic territories, often accumulated by marriage and divided when bequeathed to heirs. Dynastically legitimised empires ruled over much of Europe. This was challenged with the French revolution and ensuing democratisation: rule was no longer legitimated by God’s grace or a noble family’s dynastic claims, but by ‘the people’. A re-bordering of Europe followed in the wake of the Napoleonic conquest, restitution (with the Vienna Congress of 1815) and the new order after the First World War designed at the Paris Peace Conference (1919), which had the aim to create sovereign, democratic nation states (out of the territories of the Russian, Ottoman, Habsburg and Prussian Empires). Some of the post Paris Peace Conference borders were even decided by plebiscite – a new but never repeated phenomenon of democratic legitimation of a border.[1] The dissolution of the Soviet Union (1991) and the violent break up of Yugoslavia (1992) were the latest events changing European borders.

From Westphalia to the UN

Today, we live in a system of much smaller, but sovereign, bordered nation states. People are identified with the state, France being the state of the French and Poland the state of the Polish. This usually implies speaking a common, state language, sharing a common history and feeling a kind of belonging to the imagined community of Frenchmen and Poles. It also implies democracy: the French elect their government and the Poles theirs. Within their territory, they are sovereign: no outside power or people should interfere with their matters. ‘Taking back control’ (to the people) was the central message in the Leave-(the EU) campaign in Britain.

This idea of state sovereignty and territorial integrity argues that states should not interfere in other states’ affairs and respect their borders is core to our state system. It is a measure to sustain peace, dating back to the Peace Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, ending the Thirty Years’ War in Central Europe. The border has thus become a central element of the state to enforce its sovereignty on its territory. Article 2 (4) of the United Nations Charter states that ‘All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.’

Territorial integrity requires demarcated borders, which must not be violated. Borders allow states to exercise control. The two pictures illustrate how borders and the exercise of control can be implemented. On the left we see the fenced border between the Spanish exclave Melilla and Morocco (external EU border), while a Schengen idyl is pictured on the right, a rural border crossing between Germany and the Netherlands.

The iconic example of a fenced border was the Berlin Wall, erected by the communist German Democratic Republic in 1961 around West Berlin. Officially named the ‘anti-fascist protective barrier’ (antifaschistischer Schutzwall) by the GDR government, its real purpose was to hinder emigration of East Germans to West Berlin and West Germany, which had increased to rates destabilising the GDR’s economy. In addition to the so-called Iron Curtain separating the Socialist countries allied with the Soviet Union from Western Europe, it served as an instrument of containment and exclusion. State authorities should be able to exercise total control over all people and goods crossing the border – the GDR government also talked about a modern state border.

The Iron Curtain disappeared with the fall of Communism in 1989. Many envisioned an age of open borders and globalisation, the ‘End of History’ (Francis Fukuyama) understood as the end of ideological divides in a world of liberal democracies and free trade: a borderless world (Kenichi Ohmae). Global trade has increased manifoldly since, as has global travel. New threats of global terrorism as well as irregular migration have challenged the open borders paradigm, though. The terrorist attack on New York City in September 2001 has resulted in a revival of fenced, militarised borders. In Europe, they have become the standard at most external borders to the EU.

Schengen: open borders between sovereign states

The four freedoms of movement (persons, goods, services, capital) are the cornerstones of the European Union. To implement this, the EU has abolished checks at borders for goods and persons by pooling sovereignty within the Schengen agreement of open borders. The Schengen Code states that ‘Internal borders may be crossed at any point without a border check on persons, irrespective of their nationality, being carried out’ (Article 22). The member states have agreed on principles of control at the external borders and data sharing. The EU has established a border agency, FRONTEX, which assists member states in controlling the external borders.

The Schengen agreement, however, has not abolished borders between member states. How do they still shape our perceptions of society? The modern state border not only demarcates rulers’ taxation and juridical rights, it also describes modern welfare states with a state language, a sophisticated system of administration, education, taxation, etc. The border contains areas of different policies, building standards, infrastructure and more. Therefore, cross-border social practices are determined by much more than a lack of passport control at the border.

Research areas of B-SHAPES

Method and narratives

B-SHAPES has applied a bottom-up perspective. We have collected narratives in ten European borderlands, ranging from north to south, metropolitan and rural. Two borderlands cover external borders of the EU: Bulgaria-Turkey and Greece-Turkey.

A narrative is a story – it does not necessarily reflect the truth, but the perception of the person giving the narrative. In B-SHAPES, we aimed to collect unheard stories and voices, borderlanders’ views often being absent in national political discourses. This was evident in our data, where many borderlanders criticised national governments’ decision to close borders as a security measure during the pandemic, without taking into account the special needs of borderland residents.

Euroscepticism

Euroscepticism can mean different things: a critical attitude to the EU in general, nationalism or the idea of nation states as instrument of democratic control, but also a critical attitude to some EU policies. In recent years, Euroscepticism has often been equalised with populism, both right- and left-wing. The EU as a bureaucratic monster interfering with every detail of our lives, or, as a neo-liberal project ruining welfare states and solidarity. Brexit has been an expression of Euroscepticism, and Eurosceptic parties are represented in most national parliaments as well as the European Parliament.

B-SHAPES has been looking at Euroscepticism in border regions – by analysing border region media and interviewing candidates during the campaign for the European Parliament elections in June 2024. Surprisingly, the notion of open internal EU borders was supported by Eurosceptic candidates – under the condition that the external borders of the EU were controlled completely.

Minorities

National minorities in borderlands are often the outcome of border changes, or border delineation after the break up of multinational empires such as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. They have been separated from their kin-communities/kinstate by such historical processes.

Therefore, we assume that the border has a different meaning for them than for people fully identifying with the titular nation of the state they live in. Our research focused on border narratives in times of crisis, here the so-called migration crisis in 2015–16 and the Covid-19 pandemic. The border closures enforced during the latter (spring 2020) had an especially severe impact on the lives of borderland minorities, suddenly being cut off from their kinstate, family and friends.

Landscapes

Landscapes are not just there – humans give them meaning, which is expressed in literature and art. B-SHAPES applies this to border landscapes: what meanings have been assigned to them? What role do they play as a factor shaping our perceptions of society?

Results (preliminary)

B-SHAPES’s research has revealed that borders and border policies matter to borderland residents. The local border is a central element of the borderland identity of our participants. Living in a border region shapes their perceptions of society. Border closures experienced during the Covid-19 pandemic had a severe impact on border region residents, making them aware of how their lifestyle had been characterised by the open border regime of Schengen. The only non-Schengen border we researched, the Bulgarian-Turkish-Greek border triangle, revealed likewise that members of the Turkish community in Greece experienced border crossings very differently, with a certain nervousness.

We can also detect what we have defined as Banal Europeanisation: the EU is not identified as a key actor of de- and re-bordering, but rather as a distant institution taken for granted. The general narrative of borderlanders ties re-bordering experienced during the two crises we researched to the nation state. Cross-border heritage, on the other hand, is perceived as something local, in a binary Danish-German, Polish-Czech etc. context. The only exception is the Turkish minority in North-Eastern Greece/Western Thrace, who express a clear perception of Türkiye as a kinstate outside Europe, Greece as home state not really being European (because of its discriminatory practices against the Turkish minority) and the EU (without Greece) as being Europe – a lighthouse of welfare, democracy and inclusive minority/diversity policies.

Further reading

- Andersen, Dorte Jagetic, Martin Klatt and Marie Sandberg, eds (2012), The Border Multiple. The Practicing of Borders between Public Policy and Everyday Life in a Re-Scaling Europe. Border Regions Series, Doris Wastl-Walter. Surrey: Ashgate.

- Andersen, Dorte Jagetic, and Eeva-Kaisa Prokkola, eds (2022), Borderlands Resilience: Transitions, Adaption and Resistance at Borders. London: Routledge.

- Brambilla, Chiara, Jussi Laine, James Wesley Scott and Gianluca Bocchi, eds (2015), Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making. Border Regions Series, Doris Wastl-Walter. Surrey: Ashgate.

- Fukuyama, Francis (1992), The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press.

- Green, Sarah, and Lena Malm (2013), A Visual Journey through Periphery Frontier Regions. Jasilti.

- Klatt, Martin, and Birte Wassenberg, eds. (2018), Secondary Foreign Policy in Local International Relations. Peace-Building and Reconciliation in Border Regions. London: Routledge.

- Ohmae, Kenichi (1990), The Borderless World: Power and Strategy in the Interlinked Economy. London: Harper Collins.

- Ohmae, Kenichi (1995), The End of the Nation State: The Rise of Regional Economies. London: Harper Collins.

- Wassenberg, Birte, Bernard Reitel, Jean Rubio and Jean Perony (2015), Territorial Cooperation in Europe. A Historical Perspective. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Wastl-Walter, Doris, ed. (2011), The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies. Surrey:

[1] Taking aside the mock plebiscites implemented by the Soviet Union and Russia to annex invaded territories.