Holocaust in Romania – Introduction

Throughout the Second World War, Romania remained a sovereign state. Its authoritarian leader, Ion Antonescu, formally allied the country to the Axis powers (Germany, Italy and Japan) in November 1940. In June 1941 Romania joined Nazi Germany in Operation Barbarossa and took part in the war against Soviet Union. The main scope of Antonescu was to recover the territories lost a year before to the Soviet Union and also to create a position to regain the Northern part of Transylvania which had been ceded in August 1940 to Hungary as a consequnce of Second Vienna Award.

The genocidal actions of Romania during Second World War should be analysed independently from those of its German partner. The deportations and extermination in Bessarabia, Bukovina and Transnistria happened without any presuare from Nazi Germany and the most intense stage of this policy was in the first months of the war, before the Wannsee Conference.

This situation could be considered the aftermath of the long history of prejudices and hatred against Jews among political and cultural Romanian elite, starting from the second part of 19th century. The deportations were ordered by the Romanian government. The Romanian Army is responsible for the first stage of the killings on Bessarabia, Bukovina and Transnistria territory. In some of the localities in these regions, there were also active units of the Einsatzgruppe D who executed Jewish people independently.

The survivours of the first stage were deported to Transnistria by the Romanian gendarmerie (paramilitary police force). The Romanian National Bank and the Ministry of Finance were in charge of confiscating the belongings of those who were deported. Also, the Romanian gendarmes and police together with Romanian civil servants were responsible for the fate of hundreds of thousands of Romanian and Ukrainian Jews and the 25,000 Roma people deported in Transnistria.

The protocole of the Wannsee conference mentions the number of 342,000 Jews residing in Romania in 1942.

Roughly the numbers put forward by Adolf Eichmann for Romania are close to the estimated Jewish population in the territories administered by Romania before Operation Barbarossa and also seem to take into account the Jewish population of Bukovina that was not deported in 1941, as was the case with almost the entire Jewish population from Bessarabia. Finally in the autumn of 1942, the Romanian government decided to change its policy and suspended the plans to deport Jews from Southern Transylvania and the Old Kingdom* to the Nazi extermination camps.

The discriminatory policy against the Jewish population does not end in 1942. The ‘romanianization’ of the Jewish properties continued. Jewish men and sometimes women were subjected to forced labor, besides many other restrictions. The laws and decisions regarding the Jewish population were abolished in the second half of 1944, after Romania broke the alliance with Nazi Germany and the government of Marshall Antonescu was removed from power by King Michael with the support of some army generals and politicians who opposed Antonescu.

*Vechiul Regat (Old Kingdom) is the term used to refer for the state resulting from the unification of the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859. It lasted till 1918 when Greater Romania was proclaimed when Bukovina, Bessarabia, Transylvania and Banat joined the Romanian state.

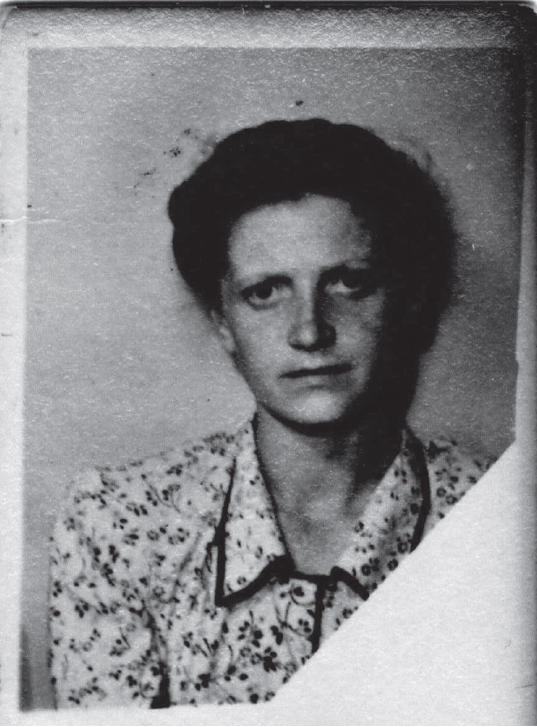

A victim story – Miriam Bercovici

Click in the photo to see the gallery:

Identity

Miriam Bercovici was born Miriam Korber on 11 September 1923 in Cȃmpulung Moldovenesc into a Jewish family. Miriam was used to living among people of different ethnicities. Her neighbours were Romanians, Germans and Jews. At school she spoke Romanian and at home German and Yiddish.

The first time her identity affected her was in 1940, when she was expelled from secondary school as were all the Jewish students enlisted in state schools. Then, in the summer of 1941 when Nazi Germany and Romania attacked the Soviet Union, the Jews in northeastern Romania had their movement restricted and had a curfew imposed on them. It became mandatory to wear the yellow star. She felt humiliated – as she mentionned later on, when she was in her 80s.

Persecution

The Romanian authorities plan was to get rid of the entire Jewish population from the Romanian soil by moving them far away in the east (in some transcripts of the Romanian government meetings the Caucasus and the Urals are mentionned but without a specific details or plan). Because the German allies objected and suggested to the Romanians to postpone the plan, in the autumn of 1941 the destination of the Jewish deportees was Transnistria. There the Romanian authorities did not offer any kind of support or assistance. The tens of thousands of deported Jews were left to chance.

The opposition of the Germans in this regard was for military and strategic reasons: the fact that large convoys of ten of thousands of Jews would be moving very close, just behind the troops and in territories not completely controlled, was a matter of deep concern for the Wehrmacht. Besides that, the Germans did not have confidence in the administrative skills of Romanians to accomplish such a big mission in an orderly and disciplined fashion.

The Romanian local authorities arranged the deportation. The deportees were obliged to hand over the keys to their houses together with all their belongings. Till the last moment most Jews did not believe that they would be deported.

Miriam was deported by Romanian authorities together with her family and almost all the Jews from Cȃmpulung county. Her parents (Leon and Clara Korber), grandparents (Abraham Mendel and Toni [Taube] Korber) and her little sister, Sylvia, were forced to leave their homes with only a small bit of hand luggage each. On 12 October 1941 a train composed of cattle cars departed from Cȃmpulung railway station with 6,118 Jews. After two days the train stopped in Atachi, a town on the right bank of Dniester, the border between Romania and Transnistria, the territory administered by the Romanian authorities from August 1941.

Soon the Romanian police take the convoys across the river at Moghilev. Here a shelter (asylum) was improvised by Jewish doctors for those deportees who were too old and sick to continue the journey.

Moghilev was unique place of deportation because the community managed very quickly to organise and negotiate with the authorities. That’s why they were able to establish such a place and also other means to provide resources. The town was a much desired place to end up for many of the deportees. Here the living conditions were better than in most of Transnistria.

The Korber family decides that the grandparents would remain under the care of the doctors here, in Moghilev. The rest of the family, like the majority of the Jews deported from Cȃmpulung, were forced to walk further to the eastern parts of Moghilev county and finally the order was to stop at Djurin. The living conditions in the Djurin ghetto were poor: Miriam shared a room with 12 other people, without toilet, heating possibilities and scarce food.

The living conditions in Transnistria, and in Djurin ghetto, were hard. Miriam and her family initially survived by selling the few things they brought from home, after that they worked when they had the opportunity, they begged and even stole food (such as beets from the fields). Even if it was forbidden to leave the locality where you were registered under the death penalty, Miriam risked her life in search of food. In time, relatives from Romania managed to send them money, but only a small amount of the help reached the family.

Excerpt from Miriam Korber-Bercovici ‘Ghetto diary – Djurin, Transnistria, 1941–1943’

Tuesday, 10 February 1942

[…] Every time there is talk that we will be pardoned (for what offense we don’t know; for the simple reason we are Jews), everything ends up in smoke and regrets. I did not think of Romania, or rather, of Câmpulung, as my homeland. That was because we were always oppressed and pushed to the side by the Romanians. But today, when we are far away, when hundreds of miles separate us from our small Câmpulung, I feel how much I miss it and how close I feel to my homeland. Heimat, how much does this word say? Our mountains, our dear mountains, where are you now? Why do you pursue me even in my sleep? Fir trees, dark forests, clean houses, handsome people; homeland, I miss you. Why are we so miserable that we don’t have a country that loves us as well! Our country has driven us away to a wasteland among strangers and among the words of persecution; some follow me endlessly: ‘Go away, wandering Jew.’

The journal

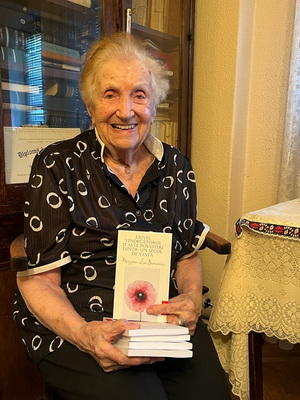

During her deportation, surrounded by misery and suffering, Miriam managed to keep a journal. Miraculously the journal was found a couple a years after the war and is a unique record of the life of those deported in Transnistria.

Miriam says in her latest interviews that her entire life was haunted by memories from Transnistria and one of the most disturbing episodes is the moment she found out that her grandparents passed away.

On 11 September 2023 Miriam celebrated her 100th birthday.