Most European countries used to have a political system that was either dictatorial or close to a dictatorship. Power was in the hands of a group of people who were not controlled by the general public. In the 20th century, political regimes in several countries became totalitarian. As the name suggests, a regime of this type aims to control all aspects of life. It is assisted in this by a secret police that puts citizens under constant surveillance. As the entire society is forced to serve the interest of the government, artistic activity is also controlled.

Each government is interested in art because the latter may be used for propaganda purposes. It is equally true for the ancient world, the Europe of Leonardo da Vinci and 20th-century democracies. This does not have to mean that creative freedom is restricted. The authorities provide funds for the works of art that are in line with their interests but do not ban those that are not. Such was not the case of Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Third Reich and the Russia of Lenin and Stalin (Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic up to 1922, then part of the Soviet Union). Most interestingly, even though all these states were totalitarian dictatorships, the situation of artists was different in each of them.

Italian writers and artists representing various movements, both traditional and modern, supported fascism, which gave them considerable benefits. The German regime, on the other hand, started combating modern art right from the outset, propagating the one that supported its ideology The ideology of Nazism was based on racial theories. They claimed that the Aryan race was superior to other races in terms of morality and civilization. Nazi art featured impeccably beautiful and strong characters who were supposed to demonstrate the ideal Aryan race, and drew inspiration from ancient Greek statues.

Each government is interested in art because the latter may be used for propaganda purposes. It is equally true for the ancient world, the Europe of Leonardo da Vinci and 20th-century democracies.

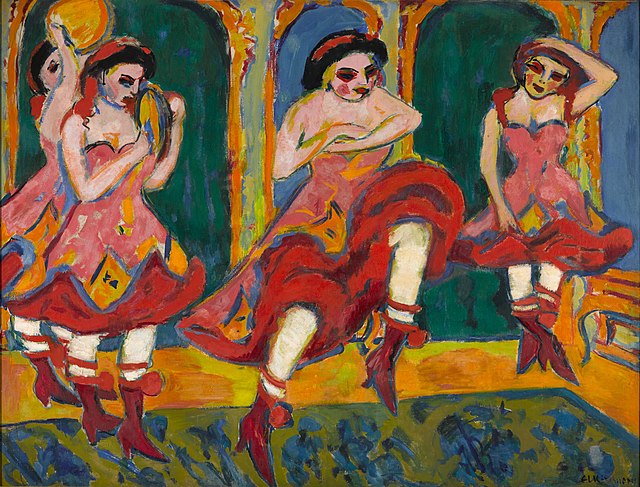

One of the movements decried as an enemy of Nazi art was expressionism, which thrived in France and Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. This is how Hermann Bahr described it in 1914: ‘Never before has this world been so deadly deaf. Never has it been so afraid. This despair screams. Art also screams, screams for help, screams for the spirit.’ The ambition of many expressionists was to express the Weltschmerz of the modern man crushed by the advance of civilization. The paintings scream with colours and sharp contrasts of deformed figures. There was no room for this kind of art in the Third Reich, a state that was to resemble a paradise on earth. Many expressionists, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde, were dismissed from art schools. Their paintings were removed from public galleries and denounced as degenerate art (entartete Kunst). The artists themselves were banned from creating works. Exhibition rooms filled up with artistic products that glorified the new masters and extolled the virtues of working for the state and combating its enemies. Rather than aspire to any new quality, this type of art tried to revive old artistic traditions but was never able to match any of them.

‘Never before has this world been so deadly deaf. Never has it been so afraid. This despair screams. Art also screams, screams for help, screams for the spirit.’ (Herman Bahr)

As for the Soviet Union and the Central European countries subjected to the Soviets after the Second World War, the relations between the authorities and art were again different. For a dozen or so years, the Soviet authorities did not restrict the creative freedom of innovative artists. On the contrary, such artists were won over to the communist ideas of transforming the state. Alexander Rodchenko, Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky and many others, but not everyone, were glad to lend their talent to the regime. Some became professors at universities. Malevich was given the function of People’s Commissar (i.e. a minister) of visual arts. The artists had no qualms about using abstract art to design ration cards or rostrums for party rallies.

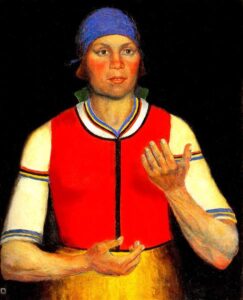

The situation changed when, in 1934, the Soviet authorities demanded adherence to socialist realist art. The term ‘Socialist Realism’ suggests that art should depict life in a socialist world in a realistic way. The problem was that, in communist countries, names never corresponded to reality. Socialist ideas, dating back to the 19th century, focused on social justice. Commonly owned goods were to be produced and shared following the principle of ‘to each according to his merits.’ Communist justice consisted in requisitioning someone else’s property such as land and factories. The aim, however, was not to share the profits with the poor sections of the society. Far from it.

The authorities spent the proceeds on armaments and social control measures, leaving only a portion of the resources (much of which were wasted) for public needs. Similarly, neither could Socialist Realism be classified as realism. As an art movement, Realism emerged in the 19th century to portray the phenomena that were glossed over by the official art commissioned by the state. The Realists liked to portray poor people, and no government wanted to put the socially disabled on display as their existence was a sign of governmental incompetence. Hence, the purpose of Socialist Realism was not to expose the shortcomings of social life. If any problems were identified, they were allegedly caused by external and internal enemies (the imperialist West as well as kulaks and regime opponents, respectively). The aim of Socialist Realism was to convince people that the communist state was on its way to a bright future.

However, life in the countries governed by the communists did not look as if it was going to improve for ordinary citizens, even though not everyone was aware of it from the beginning. Scores of modern creators, both visual artists and writers, subordinated their work entirely to the socialist realist doctrine not only in the Soviet Union (such as the already mentioned Malevich), but also in Central Europe. By writing books and poems, making paintings or shooting films that eulogized the new regime, they were complicit in deceit. The fraud was exposed when workers, a social group the communists were supposed to take care of, protested against worsening living conditions. For this they paid with their lives, like in Poznan in 1956 or Gdańsk in 1970. Many artists saw through the lies of the system and decided to emigrate. Many others, though, would never relinquish their blinkered devotion.

Suggested illustrations:

1. Kazimir Malevich, Woman Worker, 1933, State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

2. Tag der deutschen Kunst, exhibition poster, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 8–10 July 1938

3. Helena Krajewska, Youth Brigade Raised a Building in Record Time, 1949, oil on canvas, 195 × 145 cm, National Museum, Warsaw