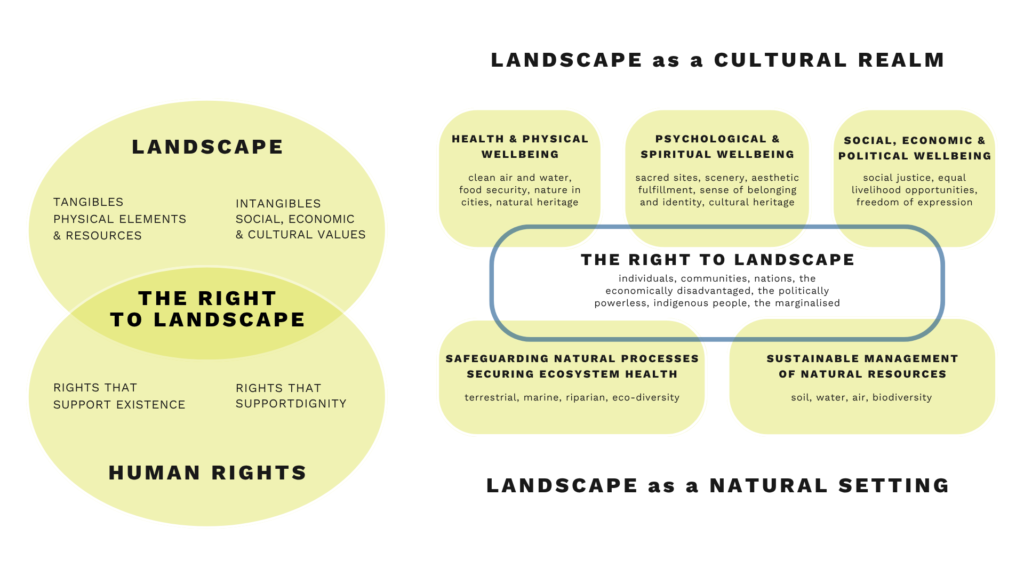

At the beginning of the 21st century, the concept of the landscape became much more important in the humanities and social sciences, as well as in local and global political discourse. Landscapes were recognised as a significant element of people’s identity, determining the physical and spiritual well-being of individuals and entire communities.

Noting that the landscape has an important public interest role in the cultural, ecological, environmental and social fields, and constitutes a resource favourable to economic activity […];

Aware that the landscape contributes to the formation of local cultures and that it is a basic component of the European natural and cultural heritage, contributing to human well-being and consolidation of the European identity;

Aware, in general, of the importance of the landscape at global level as an essential component of human being’s surroundings;

Acknowledging that the landscape is an important part of the quality of life for people everywhere: in urban areas and in the countryside, in degraded areas as well as in areas of high quality, in areas recognised as being of outstanding beauty as well as everyday areas;

Believing that the landscape is a key element of individual and social well-being and that its protection, management and planning entail rights and responsibilities for everyone.

(European Landscape Convention, 2000)

This understanding of the concept of landscape is the result of a long and complex evolution based on artistic tradition and political ideas. Over the last 200 years, it has spread across numerous fields. Consequently, it is widely accepted that landscapes are valuable elements of natural and cultural heritage. Furthermore, everyday landscapes are an important aspect of people’s reality. The complex history of the term ‘landscape’ means it is not possible to offer a single, generally accepted definition. Furthermore, different approaches use or even prefer similar terms, such as environment, place, space and territory.

Nevertheless, when it comes to studying the past, it seems advisable to adopt the following definition:

Landscape means an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors. (European Landscape Convention, 2000)

Landscape and dwelling

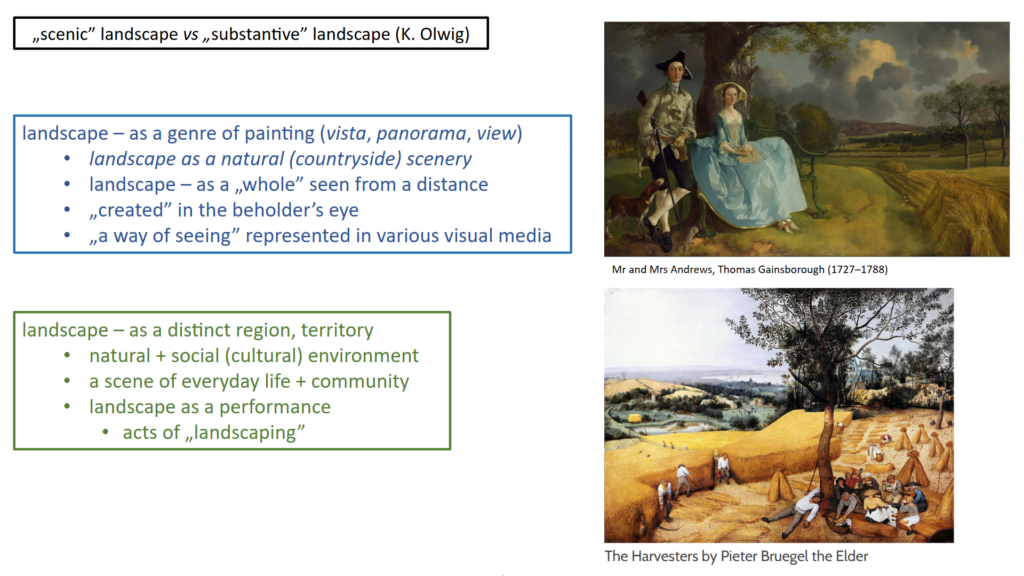

A landscape, as defined here, may be of any kind: natural (e.g. desert, forest and mountain landscapes) or cultural (e.g. archaeological, rural and urban landscapes). It may be associated with various ways of using it for different economic and social purposes, and with many ways of experiencing it. Landscapes can also be associated with different senses, not only sight, as is traditionally the case when they are treated as synonymous with views. Historically two main approaches to the concept of landscape have been distinguished, as is illustrated by, among other things, dictionary entries:

Oxford English Dictionary

Landscape:

- a picture representing natural inland scenery, as distinguished from a sea picture, a portrait, etc. the background of scenery in a portrait or figure-painting (obsolete).

- a view or prospect of natural inland scenery, such as can be taken in at a glance from one point of view.

- a tract of land with its distinguishing characteristics and features, esp. considered as a product of modifying or shaping processes and agents (usually natural).

In the context of landscape painting, the landscape is conceived as scenery that is meant to be contemplated. In this view, the landscape was expected to be beautiful or picturesque, for example. It was these aesthetic qualities that determined its value and made it noteworthy. Another approach identifies the landscape with land, which is understood as an area shaped by a community unified by norms and meanings expressed in beliefs and customs, among other things. Accordingly, the landscape is understood as a ‘scene’ with which people engage physically and spiritually. Their actions can therefore be considered ‘acts of landscaping’, and activities that inevitably impact the landscape in which they happen.

Today, some people equate the landscape with an aesthetic landscape. Nevertheless, it is generally agreed that this view is insufficient. Therefore an approach that emphasises human presence, activities and engagement with landscapes (without ruling out contemplation) has recently gained importance. This approach is believed to allow for a greater consideration of the relationships between people and the world they inhabit. This broad view is also useful when studying landscapes as the material surroundings in which people act and how they influence each other.

Landscape as …

-a result of a particular manner of looking at the world;

-a result of human work;

-an experience (as experienced sensorily by people).

(J. Wylie)

What meanings and values (apart from aesthetics ones) can you identify in the landscapes shown in the photos below?

If the landscape is the reality in which people live and act, and they experience it in ways determined by their beliefs, emotions, expectations, fears and memories, which make the landscape meaningful to them, then it must be acknowledged that landscapes combine material and immaterial elements, and the objective nature of an inhabited area is transformed by people’s subjective points of view.

[…] any landscape is composed not only of what lies before our eyes but what lies within our heads. (D. Meinig)

[…] ‛landscape’ is therefore, ‛the world out there’ as understood, experienced, and engaged with through human consciousness and active involvement. […] The same place at the same moment will be experienced differently by different people; the same place, at different moments, will be experienced differently by the same person; the same person may even, at a given moment, hold conflicting feelings about a place. (B. Bender)

Landscape and history

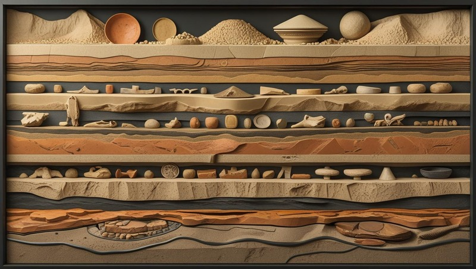

Thus, it is possible to think of landscapes as material expressions of immaterial content, such as norms, meanings and values, which determine the cultural, economic, political and social dimensions of the lives of the people who inhabit and have inhabited these landscapes. Due to their material and spatial character, every landscape is characterised by a long duration, so one could consider every landscape as being a historic landscape, which is a multilayered record of its own biography. It can also be seen as conserving the memory of past individuals and communities that have lived in it over time and shaped it in various ways through material traces. Therefore, the landscape is a kind of environmental palimpsest that preserves earlier layers, which have impacted later layers, including modern ones, and which can still be identified today.

- Landscapes are created over time, and their formation is a continuous process in which successive layers change and overlap; sometimes this process is interrupted;

- Landscapes are dynamic records of their own history

- A landscape (e.g. places, buildings, ruins, monuments, spatial layout) can “store” visible traces of past events, human activity, and history. These elements create what is known as landscape memory.

The fact that the landscape is both spatial and temporal gives it its own distinct identity and genius loci (spirit of the place). Consequently, every city is a historic landscape – its urban structure and architecture reveal how living conditions for generations of inhabitants have changed over time, and the kinds of ‘acts of landscaping’ they have engaged in. Rural landscapes also have their own histories, which can be reconstructed by paying attention not only to the current appearance of villages and towns, but also to the ways in which agricultural practices have shaped the land over decades or centuries. The memory and identity of a landscape can also be found in the landscapes seen by European explorers in the 18th century. These were environments closely related to the native communities that had inhabited those lands long before the arrival of Europeans.

Tell me the landscape in which you live, and I will tell you who you are. (J. Ortega y Gasset)

Considering that the cultural landscape is a reality inhabited by people who experience it in particular ways as meaningful, and taking into account the presence of the material traces of human activity, studying landscapes is a way to understand people’s experiences, and thus the cultural, economic, political and social factors that determine them. In other words, studying landscapes provides insight into the results of human actions and interactions with their environment, allowing us to understand people. This applies to both past and present landscapes. Consequently, it is possible to gain insight into previous eras of local history (the lower layers of a landscape) and understand why a landscape looks the way it does today and how it is experienced by its inhabitants and visitors. This enables critical reflection on one’s own experience of a landscape. For example, knowledge of how the Warsaw landscape has changed over the past 300 years, acquired through old maps and images (such as landscape paintings and postcards), as well as knowledge relating to the factors responsible for these changes (the city’s character in the 18th century, its development in the 19th century and later, the history of the Second World War, post-war reconstruction and demographic processes), allows us to understand why reconstructed buildings stand next to modern apartment blocks from the 1970s and skyscrapers from the 2000s, and why the war period is so important for the city’s identity.

Recognising and acknowledging the role of landscapes in human life leads to reflection on landscape justice. Once the landscape has been identified as an indispensable element of human existence, it follows that everyone has the right to equal access to natural and cultural resources and the right to experience landscapes in their own way. To exercise this right, people must acknowledge that others have this right too, that is, they have to have a landscape sensibility that allows them to see not only the material aspects of landscapes, but also the immaterial aspects of the present and the past. Understanding today’s world requires an understanding of the past, and insight into both can be obtained by studying landscapes.