For centuries, people debated whether painting is a more perfect form of art than sculpture. Such was the opinion of Leonardo da Vinci, but not of Michelangelo. In the 19th century, painting has definitely gained an advantage. It is paintings that marked watersheds in the development of art. They were both admired and fiercely attacked. They toured European capitals, and their creators were welcomed with flowers by crowds of admirers at railway stations. In the 20th century, however, people started proclaiming the death of painting with equal zest.

The 19th century saw the birth of two major competitors for painting: photography and film. Photographic images were much more precise than paintings. Moreover, it turned out in the 1870s that photography is a much better tool to render the movement of animals and human figures. Even more dangerous for painting was the invention of film at the end of the century. In the 19th century, it was historical painting that had the highest acclaim. The Last Day of Pompeii from 1830 by Karl Bruyllov or Nero’s Torches by Henryk Siemiradzki from 1876 were famous all over Europe. Painting panoramas was also immensely popular. They were displayed in buildings constructed specifically for that purpose so that viewers could be surrounded by the painting on all sides. Panorama paintings made it possible to depict many more episodes of the related story. The area separating viewers from the painting was additionally filled in with real earth or genuine elements of architecture. Thanks to these measures, viewers could fall under the illusion, if only for a moment, that the event was actually taking place before their eyes in real space. For all that, the scenes represented in historical painting were immobile. This gap was successfully bridged by film which put figures in motion. One of the first films, made in 1895, presented a historical scene: the execution of Mary Stuart. Even though it lasted for only eighteen seconds, it made an enormous impression on its audiences.

It was not only the new media that undermined the rationale for painting. The art was also challenged, for different reasons, by many painters.

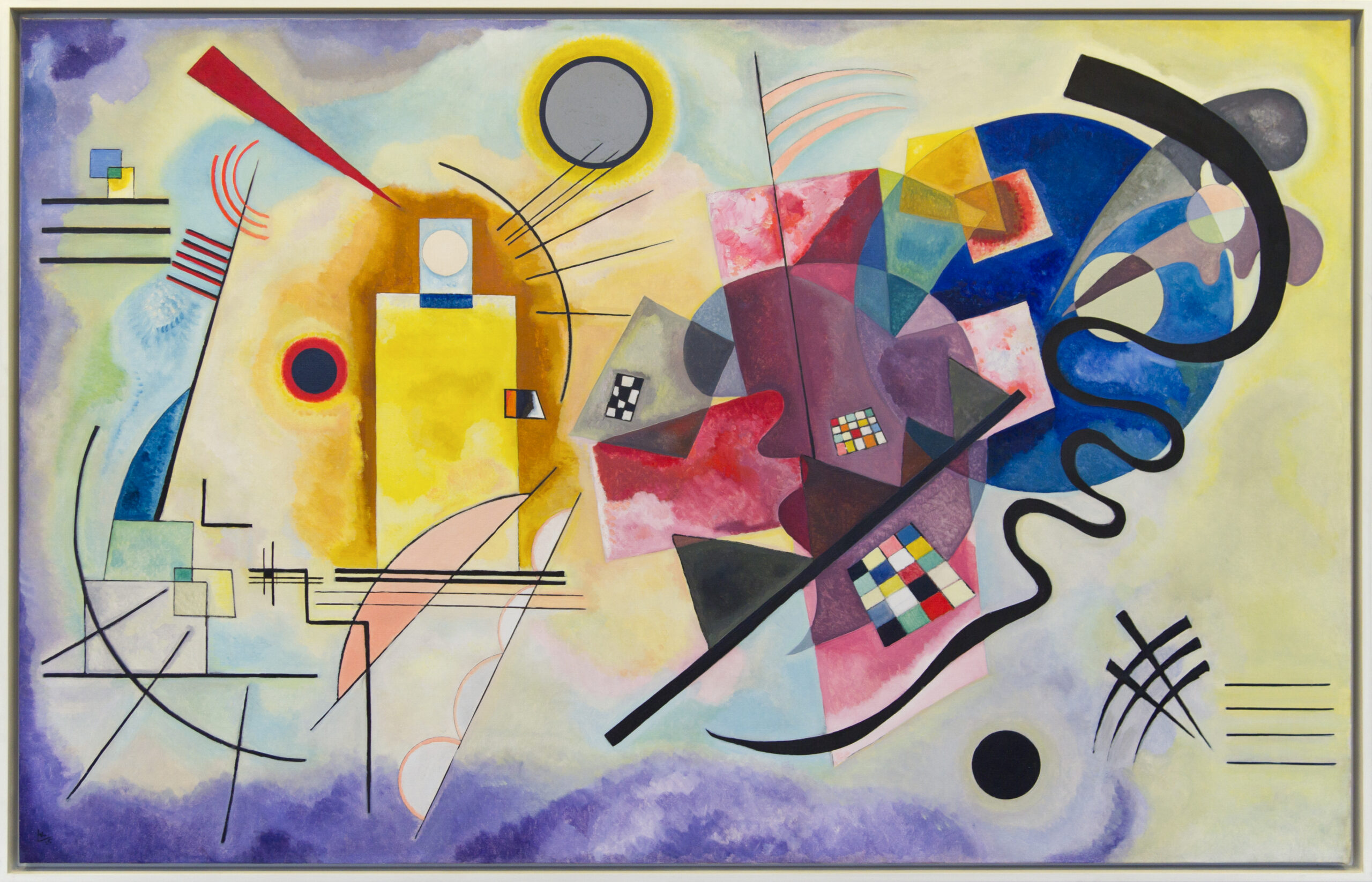

At the end of the 19th century, the Symbolists still wanted to prove painting’s superiority over photography. The advantage of painting, they said, was that it not only represented what was visible, but also suggested a spiritual depth hidden under the surface of reality. In 1910, Wassily Kandinsky decided that only abstract art can reach this spiritual dimension.

Admittedly, art looked for it in every era. This time, however, its purpose was to unveil what was previously unknown. The artist, like Moses, was to proclaim new truths to the world. Kazimir Malevich wanted to go further and create paintings whose message was unknown to the painter himself. The artist was to guide mankind through the world that was yet to come. Malevich expressed this radical idea by painting his Black Square on White Background in 1913. The artistic experiments undertaken by Malevich, who was active in Russia, coincided with the political coup in this country. The aim of the October Revolution was to create the first communist state in the world, a state that would lead mankind to a better future.

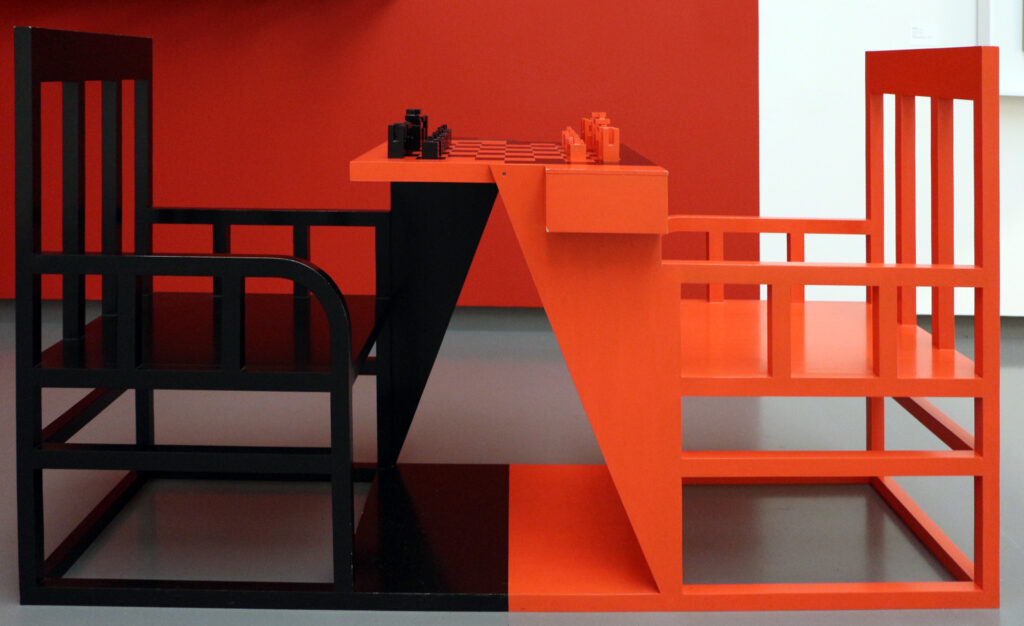

What was the fate of painting after Malevich’s radical step? It could either go back to its old rut or be removed. The latter solution was chosen by the Russian painter Alexander Rodchenko who painted three single-colour paintings. He wanted paintings to be no different from ordinary objects. Rodchenko believed that the role of artists was not to create exceptional things. Their works were supposed to have the same value as mass produced goods. Artists were to be like workers, contributing to social progress, a role that, according to Rodchenko, could not be filled by painting.

The Polish artist Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz also abandoned artistic painting, but his reasons were totally different from Rodchenko’s. Witkiewicz was in Moscow in 1917 during the outbreak of the October Revolution. His saw crowds of people blinded by ideology and controlled by demagogues. He also noticed that social life was more and more subordinated to the industrial mass production of goods. He believed that these changes turned people into slaves who were no longer able to experience metaphysical feelings related to other aspects of reality.

The suggestion to treat a work of art as a commodity was still raised after the Second World War. In Western Europe, however, it was accompanied by unprecedented criticism of painting.

According to Witkiewicz, the social and political situation left its mark on painting too. In his opinion, painting was much simpler than in former times and modern art lost its ability to transport people into the realm of the spirit. Art had become just another product available on the market. This is why Witkiewicz began to produce paintings that he treated as a regular commodity. In 1925, he started a portrait-making business and made it his means of sustenance. He drew up the Terms of Service whose motto was: ‘The customer must leave satisfied. Misunderstanding is not an option.’ In order to avoid misunderstandings, he suggested seven types of portraits with different price tags. Type A, for example, was described as ‘relatively the most “licked-down.” More suitable to female than male faces. The finish is “smooth” with a slight loss of character to the benefit of embellishment or highlighting “prettiness.”’ Those who commissioned portraits knew in advance what they should expect. Paintings were not supposed to take the customer into the unknown, but to satisfy his needs and tastes. It is unlikely that Witkiewicz expected these portraits to be considered his top painting achievements in the years to come.

The suggestion to treat a work of art as a commodity was still raised after the Second World War. In Western Europe, however, it was accompanied by unprecedented criticism of painting. It was believed that each painting, regardless of its size, was inevitably a commodity. Painting became an alleged enemy of independent and free art. The desire to be free should not be made light of, but it would be a mistake to claim that a work of art that can be sold has lost its value. Most famous paintings have been made for money. In the course of centuries, painters have often complained that those who commission paintings restrict their creative freedom. This discomfort will probably always be felt by artists, but those who are truly eminent were and will be able to deal with it.

Suggested illustrations:

1. Alexander Rodchenko, Triptych, 1921, Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepánova Archives, Moscow

2. Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Portrait of Ms Żukotyńska. Sphinx, 1928, pastel on paper, 65.6 × 47 cm, Museum of Central Pomerania, Słupsk