Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 13 in B-flat minor ‘Babi Yar’ features poetry by Yevgeny Yevtushenko. In the first movement, the composer refers to the poem Babi Yar, which describes the tragic fate of the Jews murdered in a ravine near Kiev. This mass murder perpetrated by the Nazis remains one of the most gruesome symbols of the Holocaust: on 29 and 30 September 1941, right before Yom Kippur, the Germans murdered over 33,000 Jews in Babi Yar.

The oeuvre of the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–75) includes a handful of works directly connected with political and historical events. For example, Symphony No. 7 ‘Leningrad’ (1942) and Symphony No. 8 (1943) were inspired by the tragedy of the Second World War, while Symphony No. 11 (1956–57) is subtitled ‘The Year 1905’, and No. 12 (1959–61) is known as ‘The Year 1917’. Shostakovich dedicated his Second and Twelfth Symphonies to Lenin, received a Lenin Prize for the Eleventh (1958), and depicted the siege of Leningrad in the Seventh – the latter theme comes to the fore, for example, in the famous ‘invasion episode’ (no wonder the piece is sometimes referred to as a ‘symphony of rage and combat’ or the ‘Eroica of modern days’). The story behind the composition of the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1932) and the problems surrounding its premiere could serve as a canvas for a separate book and exemplify the direct impact that politics can have on art. It is therefore not surprising that Shostakovich’s biography inspired the historian Brian Moynahan to write a monumental volume entitled Leningrad. Siege and Symphony (2014), and Julian Barnes to pen his novel The Noise of Time (2016).

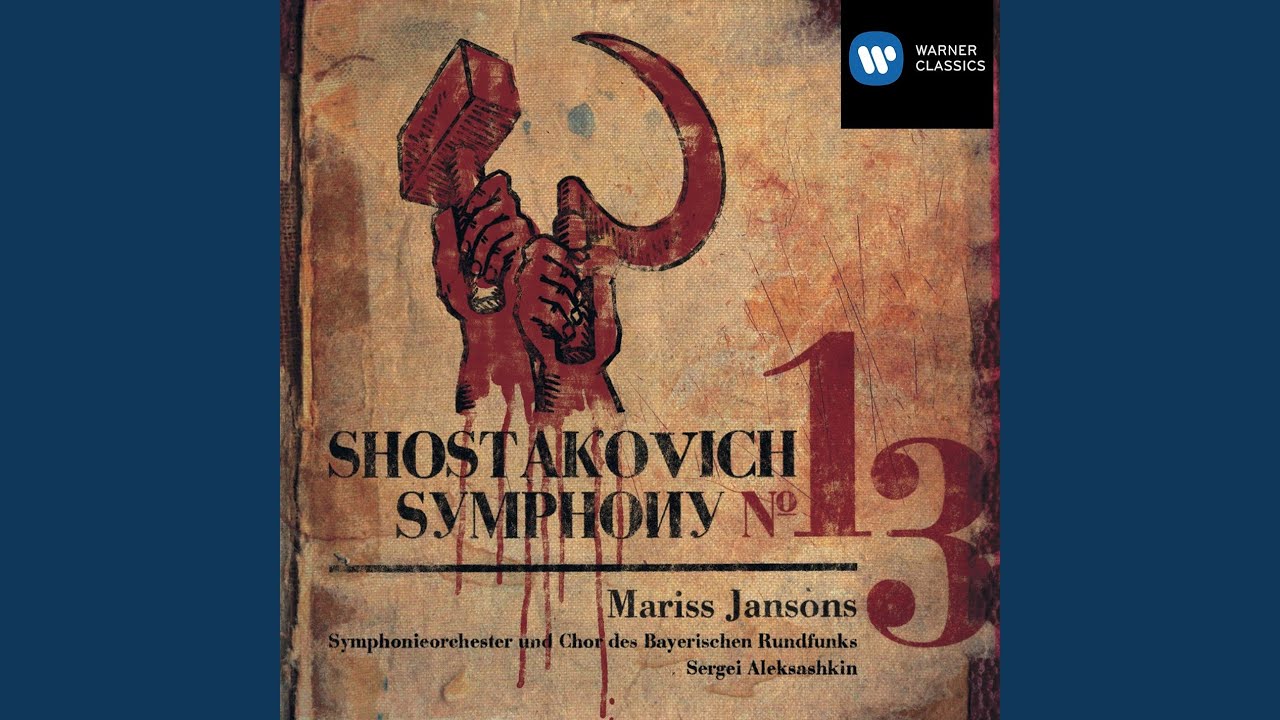

Special attention should be paid to Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor ‘Babi Yar’ (1962), for bass solo, bass choir and symphony orchestra. Shostakovich set about writing the piece in March 1962. He started from the first movement, which given the historical context is perhaps the most interesting. The composer based the composition on a poem by Yevtushenko – Babi Yar – about the gruesome slaughter of Jews in a ravine near Kiev. The poem was highly controversial at the time.

This act of mass murder committed by the Nazis still remains one of the most gruesome symbols of the Holocaust: on 29 and 30 September 1941, and thus on the eve of Yom Kippur, which is one of the most important Jewish holidays, the Germans massacred over 33,000 Jews in the Babi Yar ravine. ‘When people handed over their valuables and documents,’ writes Professor Timothy Snyder in Bloodlands, ‘people were forced to strip naked. Then they were driven by threats or by shots fired overhead, in groups of about ten, to the edge of a ravine known as Babi Yar. Many of them were beaten. […] They had to lie down on their stomachs on the corpses already beneath them, and wait for the shots to come from above and behind. Then would come the next group. Jews came and died for 36 hours.’ To this day, despite the fact that the Russian authorities have never raised a memorial at Babi Yar, it remains a place of a pilgrimage for Russian Jews.

The music has no match – and not only among Shostakovich’s pieces. It follows every word like an investigator, step by step, shadow by shadow, and the listener – due to the illustrative character of the piece – yields to it as if hypnotized.

Conservatives accused Yevtushenko of a lack of patriotism and criticized him for his one-sided approach to the subject, i.e. describing only the wretched fate of the Jews, without mentioning the other nationalities that perished near Kiev. Hence, Shostakovich’s decision to use the poem was a particularly brave one. The premiere of the symphony was planned for 18 December 1962; however, several days earlier, in a meeting between Nikita Khrushchev and representatives of artistic circles, Yevtushenko accused the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union of supporting antisemitism. The consequences were unavoidable: the publication of Babi Yar was stopped, and there was mounting pressure to postpone the premiere of the symphony.

On 18 December, ‘so many people gathered in front of the entrance to the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatoire,’ writes the Polish composer and Shostakovich’s biographer Krzysztof Meyer ‘that at some point the entire square was surrounded by the citizen’s militia. However, so many people had already managed to enter the building that the spacious interior of the Conservatoire could hardly fit them all. Only the government box remained empty. […] From the first bars, the audience listened to this tragic, powerful and dynamic music with great attention and emotion. They listened out for every word, despite the fact that contrary to custom, the poem had not been printed – for this the authorities would not give their consent’. When the first movement ended, there was rapturous and spontaneous applause.’

The music has no match – and not only among Shostakovich’s pieces. It follows every word like an investigator, step by step, shadow by shadow, and the listener – due to the illustrative character of the piece – yields to it as if hypnotized. First, the bass choir sings dramatically in unison: ‘No monument stands over Babi Yar / A drop sheer as a crude gravestone / I am afraid / Today I am as old in years as all the Jewish people’ (translation from: The Collected Poems 1952–1990 by Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Edited by Albert C. Todd with the author and James Ragan. Henry Holt and Company 1991, pp. 102-104.). The instrumental accompaniment here is a masterpiece. Later, the soloist appears: ‘Now I seem to be a Jew / Here I plod through ancient Egypt / Here I perish crucified on the cross / and to this day I bear the scars of nails‘. The best opera theatres would not be ashamed of this melody – there is so much tension and power in it.

In subsequent verses various events are fast-forwarded, as if on a movie reel: the Dreyfus Affair (the French officer of Jewish descent unjustly sentenced for state treason at the turn of the 20th century), Polish pogroms of Jews in Białystok, the tragic story of Anne Frank (the young author of the moving diary, who died in a concentration camp) and the massacre at Babi Yar from which the symphony gets its name. In the finale of the first movement, the soloist sings: ‘In my blood there is no Jewish blood / In there callous rage, all antisemites / must hate me now as a Jew / For that reason I am a true Russian!’ No-one should remain indifferent to this music and these words.