The text of Krzysztof Penderecki’s Death Brigade comprises selected fragments of an amazing and terrifying document written during the Second World War. The document is The Death Brigade (Sonderkommando 1005) by Leon Weliczker, a journal written by a Jew inducted into a Sonderkommando (Special unit) and forced to cover up the traces of Nazi crimes by unearthing and burning the bodies of victims in 1943 in the area of Lviv. The rest is made up of brilliantly combined sounds of instrumental and electronic music, including sounds of a beating heart.

This music is not supposed to be pleasant. Its aim, rather, is to cause pain – physical, mental and psychosomatic. Its predilection for what is ugly, visceral and bloody brings it close to the poetry of Tadeusz Różewicz or the paintings by Francis Bacon who ‘managed to transform / The crucified person / Into hanging dead meat’ (Tadeusz Różewicz, Francis Bacon, or Diego Velázquez in a Dentist’s Chair, 1994–95). The Death Brigade is like films such as Stanley Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange, Michael Haneke’s Funny Games or Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. The problem is that these are nonetheless part of show business (which cinema essentially is). Penderecki’s music in the Death Brigade is not.

Before we analyse the music further, however, it is worth mentioning a special place on the sound map of the 20th century – the Polish Radio Experimental Studio (PRES). We need to remember that there was a time in the history of music and technology when it was not possible to produce sounds by means of the little box called the smart phone. As the interest in generated sounds and concrete music was growing, PRES and other such places responded to the new requirements of the audience.

The studio was set up in 1957, ten years after the studio in Paris, six years after the one Cologne and two years after the one in Milan. It was therefore the fourth professional electronic music centre in Europe. For twenty-eight years, until 1985, the founder of PRES and its head was Józef Patkowski, an eminent musicologist, acoustician, initiator of music events and, later, long-standing President of the Polish Association of Composers. It was in PRES that the first Polish tape piece was made in 1959: A Study for One Cymbal Stroke by Włodzimierz Kotoński (originally a soundtrack for Albo rybka…, an animated film by Hanna Bielińska and Włodzimierz Haupe).

This music is not supposed to be pleasant. Its aim, rather, is to cause pain – physical, mental and psychosomatic.

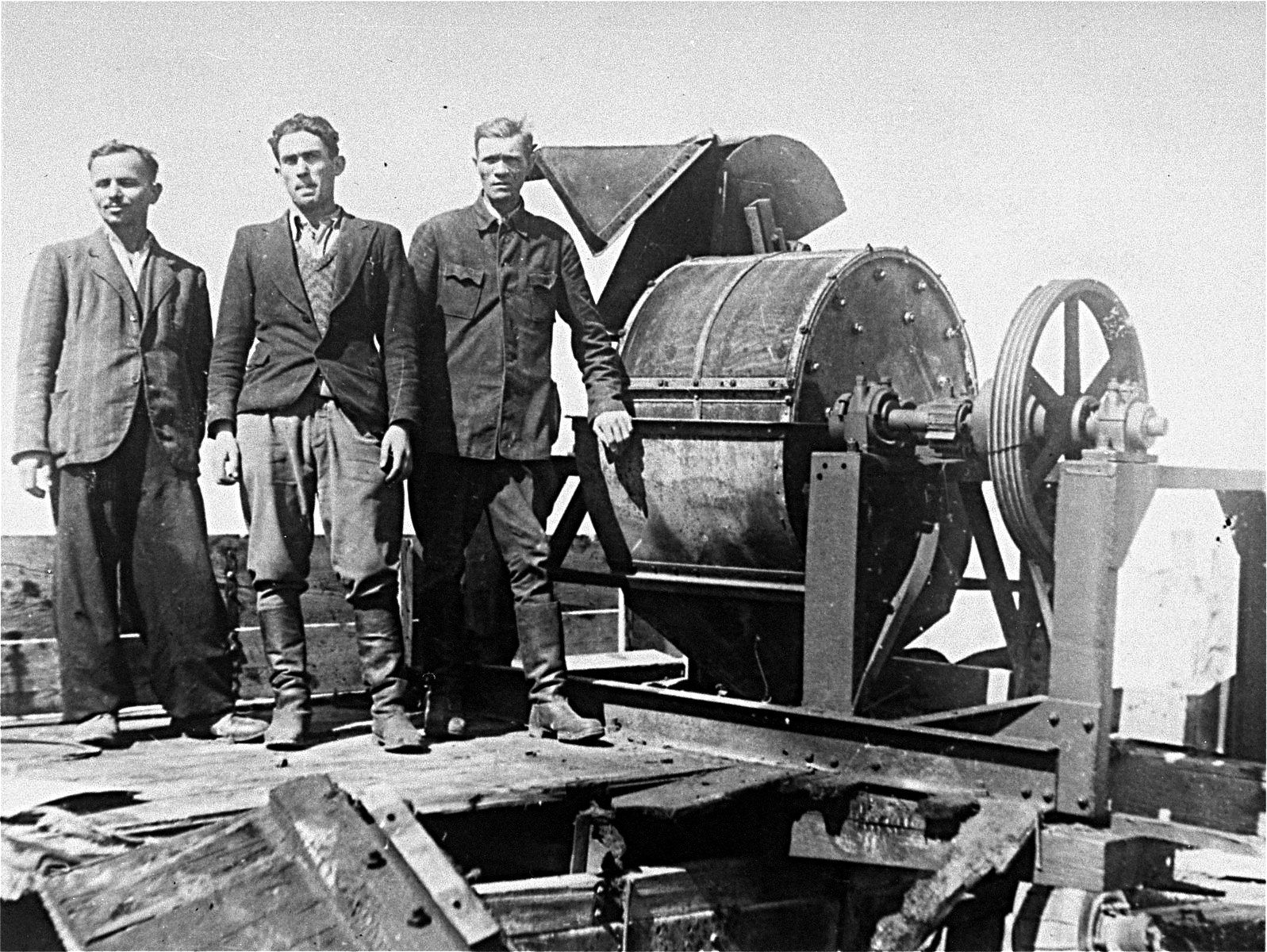

It was also there that, in 1963, Penderecki generated his thirty-minute-long Death Brigade (combining recitation and tape music) in cooperation with Eugeniusz Rudnik (the legendary sound engineer who died in 2017). The text consists of selected fragments of an amazing and terrifying document written during the Second World War. The document is The Death Brigade (Sonderkommando 1005) by Leon Weliczker. It is a journal written by a Jew inducted into a Sonderkommando (Special unit) and forced to cover up the traces of Nazi crimes by unearthing and burning the bodies of victims in 1943 in the area of Lviv.

Here is a fragment of the text: ‘We are standing among dead bodies in a tight formation, surrounded by blood clots. We don’t know whether we’re waiting to be killed or taken to spend yet another night in the death prison like the three brigades before us. Our “Ober Juden” Herr Fess reports the headcount. There are forty-two of us. We can hear “Rechts um.” Everyone turns right. But the turning is not as brisk as in the camp because of the dead bodies strewn about us. […] We fall silent, looking at one another. We can hear the sounds of music that accompanies people on their way back to the camp. It is raining. I wake up. I can hear moaning. Another cursed day! It is seven o’clock. The leader of Schutzpolizei shouts “Raus!” We all come out. We sit on the ground in groups of five just like yesterday evening. Zechsführer counts us – the number is correct. They give us twice the camp ration of bread and one litre of sweet coffee. We get up, lock our arms and march the same way we got here yesterday.’ Faced with this detailed, dispassionate and matter-of-fact account, the listener is left defenceless and helpless.

‘We are standing among dead bodies in a tight formation, surrounded by blood clots. We don’t know whether we’re waiting to be killed or taken to spend yet another night in the death prison like the three brigades before us.’

Wieliczker’s words are read by Tadeusz Łomnicki, one of the most eminent Polish actors of the second half of the 20th century. His voice – direct, controlled, passionate and clear – stays etched in the memory forever; each phoneme and syllable have their own colour and shape. The work is completed with a brilliant combination of electronic and instrumental sounds, including a heartbeat. They are far from being illustrative. According to Eugeniusz Rudnik ‘Penderecki’s greatness is that we managed to resist the temptation of naturalism and didn’t show skulls cracking open in a roaring fire, […] the author’s text is multiplied ever so subtly, intelligently and delicately.’

Before its planned radio première (intended to mark the 20th anniversary of the Auschwitz-Birkenau liberation), the work was performed publicly in the Chamber Hall of the National Philharmonic on 20 January 1964. It was accompanied by visual effects created by blue and red floodlights. The audience left the spectacle in silence, but the reactions of listeners were such that the work was not presented again until forty-seven years later.

Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, a writer and editor-in-chief of the Twórczość monthly made the following comment about the event: ‘Presented before an audience seated on comfortable chairs in the warm concert hall, the thing seemed to address the worst human instincts’ (article ‘Proportion and Weight’). Zygmunt Mycielski, a composer and editor-in-chief of Ruch Muzyczny, wrote: ‘I am surprised that an artist of Penderecki’s standing would mix a realistic document with an attempt at creating an acoustic framework that immediately suggests a work of art. Art ends where genuine realism begins’ (article ‘Misunderstanding’).

The Death Brigade was performed again during the Warsaw Autumn festival in 2011 (also in the Chamber Hall of the National Philharmonic, although without the red and blue floodlights) in absolute silence. In deep concentration. With no colours.