Sofonisba Anguissola, Artemisia Gentileschi or Berthe Morisot are among the best known names in the history of European painting. Yet it is difficult to recall other names of female painters. Those with a better knowledge of the art of their own nation can probably name a few more. Answering the question ‘Why were there no great female artists?’, one can clearly answer: women were often not given a chance to develop their talents. State universities were closed to them. A situation that changed only in the 20th century.

In the 19th century, women still could not study at state art universities. The only option left for them was private schools, often abroad. Many Central European female artists went to study at Akadémie Julian in Paris. It was not surprising that Anna Bilińska had dreams of establishing a school for women in Warsaw. Male artists studying at public schools received bursaries to go abroad. Female artists did not enjoy such support, a fact which restricted their opportunities to rent larger ateliers. Small premises, in turn, did not allow them to paint large pictures which were typically a ticket to fame and money.

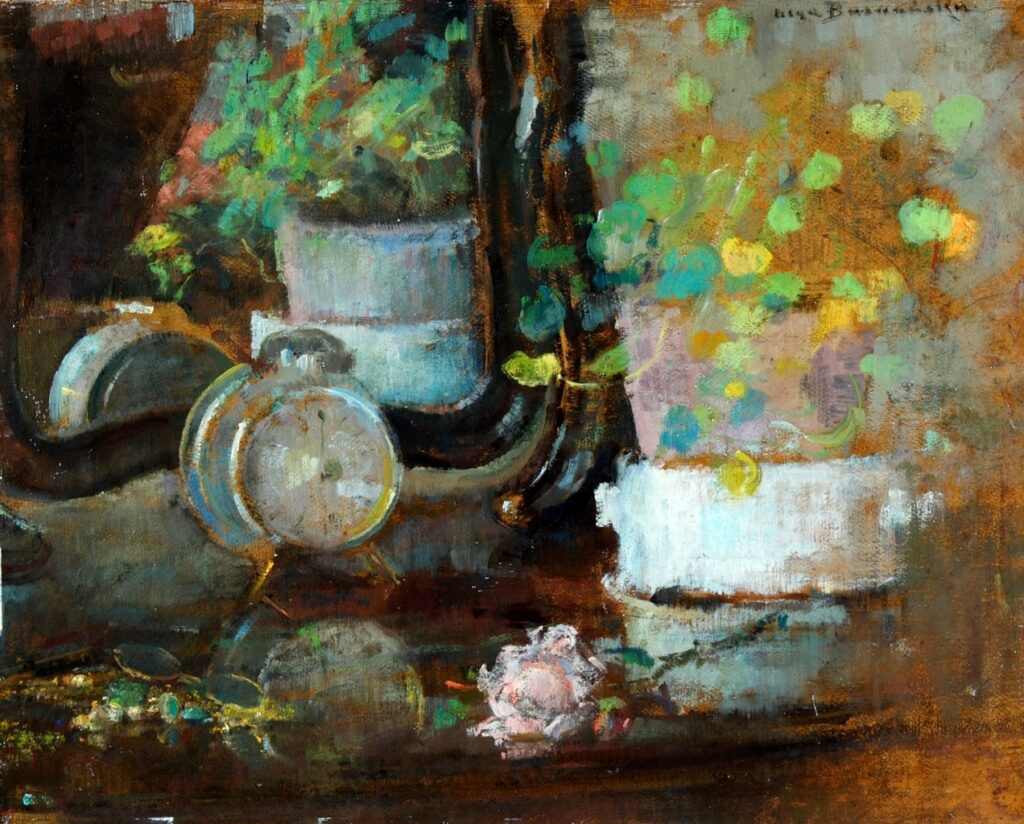

In summary, women’s opportunities in terms of educational path and career development options were limited. Paradoxically, sometimes the lack of university access was beneficial – after all one could also squander talent in a bad school rather than develop it. The inaccessibility of education was most probably a saving grace in the case of the Polish painter Olga Boznańska, as in the late 1800s the artistic school in her hometown Kraków was considered to be very conservative and closed to new phenomena in art.

The difficult situation for women changed only at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, when art academies opened their doors to female students. Yet they were not immediately allowed to paint male nudes (for reasons of morality) and they had to improve their knowledge of human anatomy by studying female nudes. The female body also thus featured in their works more frequently. The painting tradition – from antiquity until the 19th century – abounds primarily in images of the female body created by men. They are very common particularly in works with mythological themes: the bath of Venus, the judgement of Paris or Diana hunting.

The women on such canvases looked the way men wanted to see them. After all, both the painter and the commissioning party were mostly men.

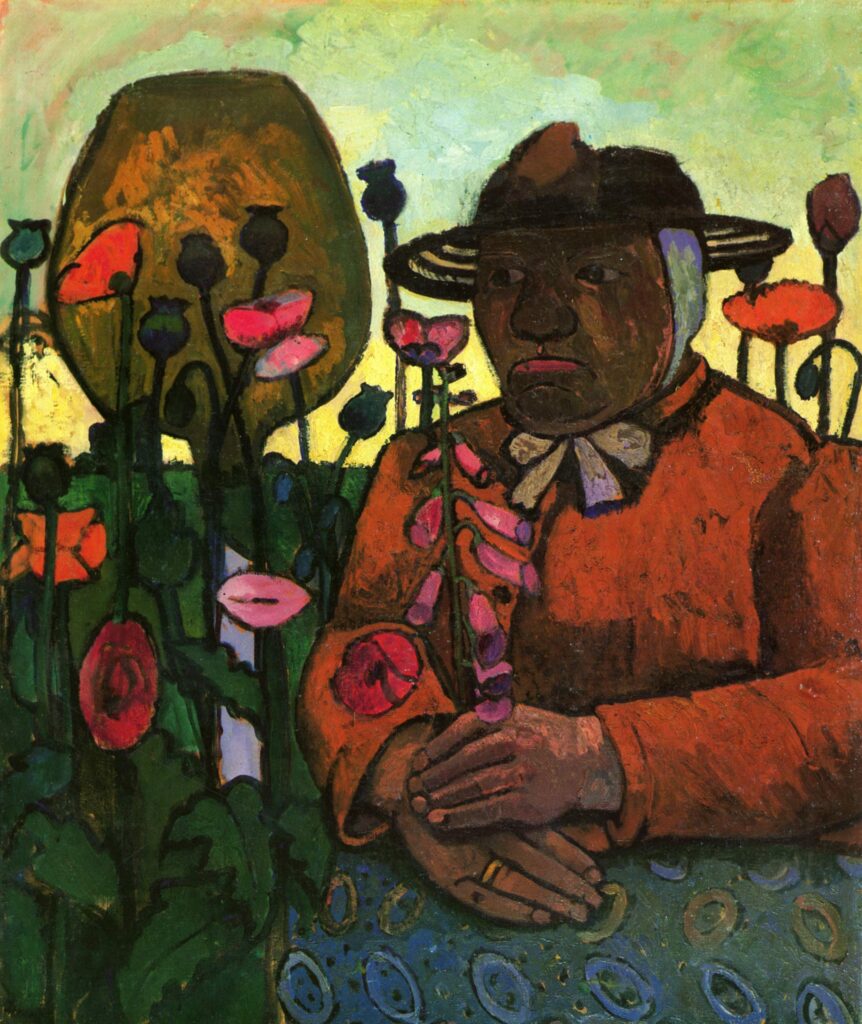

In the 20th century, female painters could then find inspiration exclusively from pictures that were a reflection of a man’s perspective on things. However, it seems that over time more and more female artists began to look at the female body through their own eyes seeking to go beyond traditional conventions. Paula Modersohn-Becker’s works are a good example of this. The German artist showed pregnant and breastfeeding women. She did not paint beautiful bodies that were idealised or destined to be admired. She presented women whose bodies change due to their specific biology. Her paintings express the bodily experience available to women only. Pregnancy, birth-giving and breastfeeding were still treated as shameful and as a taboo, which is why Modersohn-Becker’s works are exceptional in the first half of the 20th century. Most female artists of the time were keen to paint children but not scenes of motherhood.

Changes in art schools were taking place relatively fast. At the Kraków School of Fine Arts for Women run by Maria Niedzielska, students followed a course where already in 1912 they could draw male nudes. One pretext to show the male body was sport, that was gaining popularity at that time. The culture was changing dynamically. The turn of the 19th and 20th centuries was characterised by pessimism, the omnipresent disbelief in man’s ability to find happiness and the presence of meaning in human life. In the 1920s, the ideal to pursue was harmony between the body and the spirit. It was believed that this could be achieved by practising sport. Maintaining hygiene and attention to the body were treated as modern man’s duty. Sports scenes were painted by both male and female artists, yet it was women who had better results. Male painters lent too much heroism and battle-like dimensions to sporting scenes while female painters managed the theme more freely, as greatly exemplified by Maria Ewa Łunkiewicz’s 1936 painting Football.

Of special importance for understanding the situation of female artists and their art in the 20th century is the fact that for a long time they painted very few self-portraits. Mass culture was dominated by images of women created by men.

Journals would feature on their covers faces of attractive girls to attract readers. Women’s feelings or thoughts did not matter. A female face was primarily something to be liked. As women were not treated like empowered individuals, it seems that the low number of female self-portraits reflected female artists’ reluctance to make their own images part of the convention. Female artists did not want to conform by making a show of their faces.

The few women who did paint their own appearance did so in order to assert a distance from mainstream convention. One example is Self-Portrait by Maria Ewa Łunkiewicz (1930). The person shown has no eyes, just blue eye sockets. She resembles more of a dummy used in shops to showcase attractive clothes. ‘This is what I am to you’– the artist seems to be saying to the audience of her time.

Women’s art in the 20th century was subject to many changes as the social context was changing. At the same time, it constitutes a separate and important subject. It is to a large extent an expression of the desire to make sure that images are produced that differ from those painted by men and that the creative output of female artists becomes a reflection of their separate, female experience.